The Cacophony Of Raymond Pettibon

Words by Jamie Brisick

On a bright morning in his Venice Beach studio, Raymond Pettibon ponders his wave painting-in-progress.

Seen from a high perch, a pier maybe, a vibrantly blue lefthander crests, the white lip about to hurl forward. An adept surfer might whip around and catch it in a single stroke, or perhaps none at all.

“The economy of means is one of the best things that drawing has going for itself,” he says between sips of coffee. “The great masters of drawing tend to have that elegant line. That tends to be an ongoing struggle with me within each individual work. I’ve done a number of waves before, but the point of view or take on it can get old. So I try to differentiate from that. When you can do something that seems new, the economy of the sublime—that’s what I’m trying to do.”

Tall, shaggy, and bear-like, Raymond wears a russet tee, oversized grey check trousers, and no shoes. He speaks softly, slowly, with long, ponderous pauses. Much like the words that punctuate his drawings (“Some pieces I’ll work on for decades,” he says.), he’ll begin a train of thought, retract it, and start anew. You can almost see his mental eraser rubbing away, his furrowed brow searching for the pith. He is not one for eye contact, and mid-sentence he’ll sporadically dart across the room to rearrange something, then come back and pick up where he left off.

Raymond’s studio is a white-walled former furniture showroom on traffic-heavy Lincoln Boulevard. It exudes a certain ‘ransacked by the DEA’ appeal. Dirty socks, weathered LPs, pulp novels, surf magazines, cruiser bikes, and vintage baseball mitts share floor space with his dachshund mutt, Barely Noble.

Strewn haphazardly about his worktable are newspapers, tubes of paint, lidless inkpots, a wooden baseball bat, loose CDs, an open bottle of rosé, and tortilla chips and salsa, all of which sit precariously close to or atop valuable half-finished drawings.

““I’ve known Raymond a long time,” says legendary bass player Mike Watt. “He’s probably one of my greatest teachers and best friends. I love him to death. I met him on the punk scene and he did the artwork for the first Minutemen record.”

Taped to the wall are works-in-progress: a buxom topless woman with a death mask, a man kissing an outstretched hand, a child’s red wagon, an apish arm and leg, a bent over, naked woman with “This is too forward, Trick,” scrawled above, and the feathery blue wave that he broods over.

“My favorites are the ones that have some lyrical space beyond a strict interpretation,” he says, “the ones that I couldn’t put into any descriptive terms what I was doing.”

* * *

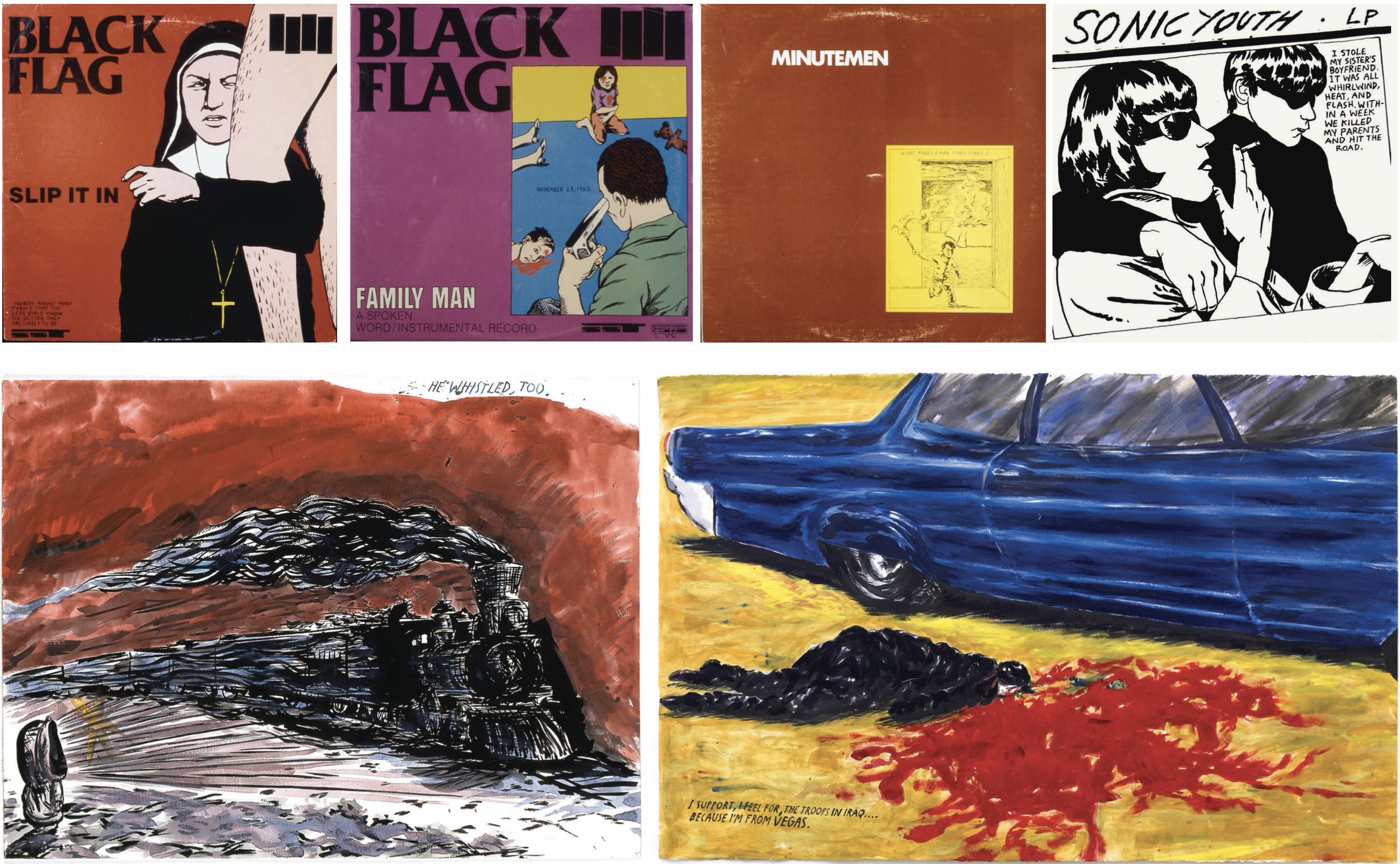

Born in 1957 and raised in Hermosa Beach by academic parents, Raymond’s childhood was filled with books, comics, basketball, baseball, and surfing. When his brother, Greg Ginn (Ginn is the family name, Pettibon is Raymond’s nom de plume), formed seminal punk band Black Flag in 1976, Raymond was appointed chief graphic designer. He first designed their famous logo (four black bars), and then a slew of album covers. He also published ‘zines of his text and drawings with catchy titles like “Tripping Corpse,” “The Language of Romantic Thought,” and “Virgin Fears.” For much of the next decade he remained decidedly underground, exhibiting in small galleries and record stores.

But as his work evolved, so did his audience. In the mid-‘80s a handful of renowned LA artists—Mike Kelley, Jim Shaw, Paul McCarthy, and Ed Ruscha among them—embraced Raymond, and subsequently a number of key collectors and curators. Soon he would occupy an almost contradictory post. He was a bona fide global art star, his drawings and paintings shown in prestigious galleries and museums. He was also a DIY/indie icon. Though he’d graduated with a degree in Economics from University of California, Los Angeles in ‘77, he was essentially self-taught. His medium required nothing more than a piece of paper and a pen. He ran with jazz musicians, barflies, Mike Watt of the Minutemen. He did not drive, but rather rode public transport, often scribbling away at the back of the bus. To top it off, he still lived with his parents in the home he grew up in.

“Raymond has read everything. He has an incredible memory. He’s been a subscriber to Surfer or Surfing for many years, and he reads about spots and he remembers. Raymond knows the right tide, wind, and swell direction for all the best spots around the world. It’s like he’s from another planet.”

In 1990 he created the cover art for Sonic Youth’s Goo. I remember it vividly; it presided over the bed I shared with my first girlfriend. A black-and-white illustration of a pair of young, mod-looking lovers in dark sunglasses, the girl at the wheel, the mood vaguely sinister. In the upper right corner the text reads, “I stole my sister’s boyfriend. It was all whirlwind, heat, and flash. Within a week we killed my parents and hit the road.” At the time I saw it as the perfect metaphor for our newfound love. After our colossal break up I would learn that it was in fact based on a paparazzi photo of a married couple en route to the famous “Moors Murders” trial in England. Raymond’s work moves in mysterious ways.

His subject matter includes Charles Manson, surfers, baseball players, vixens, homicidal teenage punks, Elvis, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, and the cartoon figure Gumby, who has the miraculous ability to walk into a book and enter a story (an alter ego, perhaps?). His stock-in-trade is the marriage/collision/disconnect of image and text. Some pieces do this in a wry, straightforward manner; others are like great song lyrics: they could be interpreted a thousand different ways, and none would be wrong.

“The ideas came out of reading,” he said in a 2001 interview with Dennis Cooper in LA Weekly, “and they were kind of between the lines, or suggested. It’s kind of like swimming in words and letters. I place myself in this state of consciousness where I’m receptive to associations.”

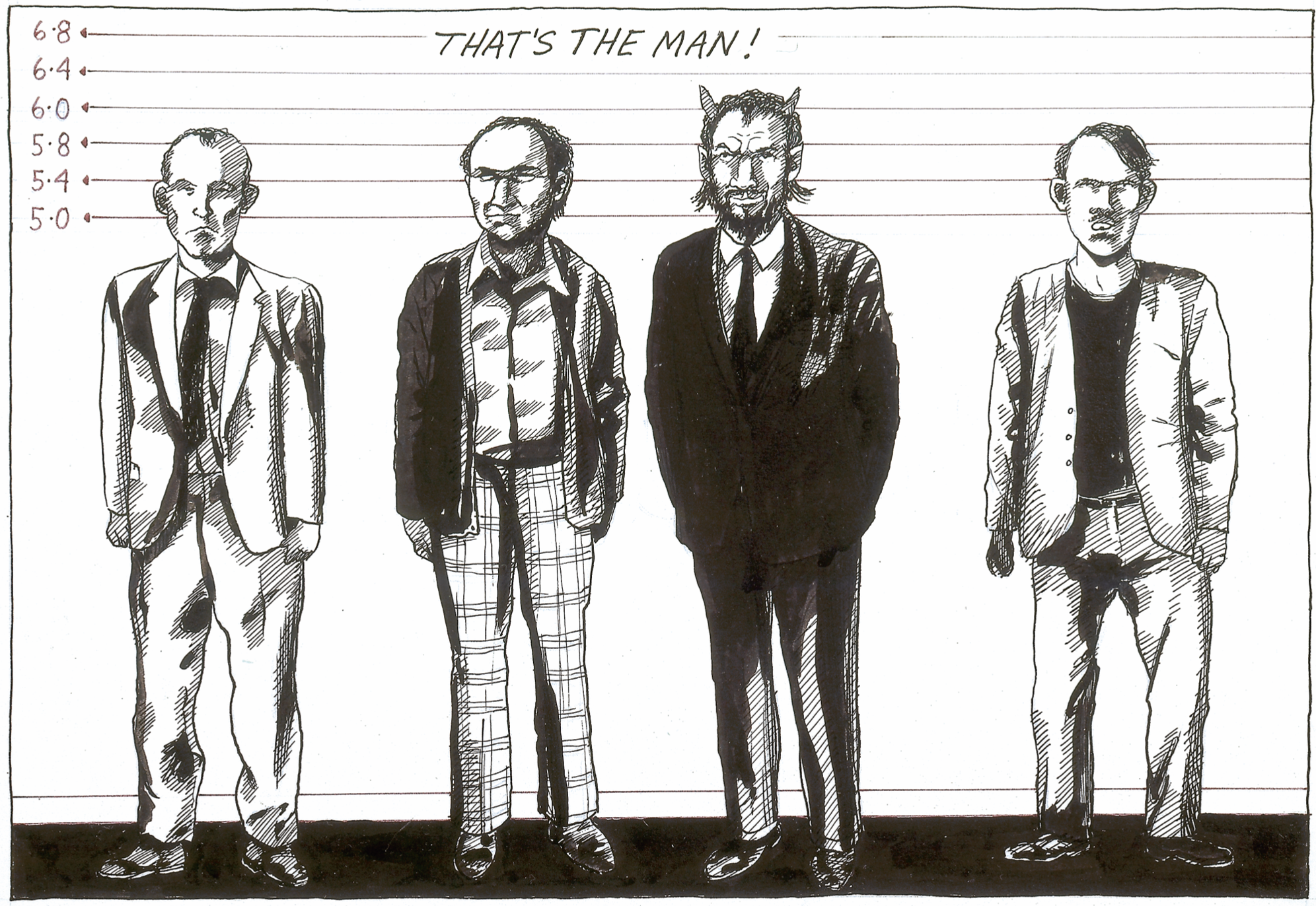

Raymond’s early work generally employed only one or two lines of text. But as the ‘80s wore on he expanded into three or four, often in a cacophonous manner that suggested disparate voices. As Oscar Wilde famously put it, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth.” Raymond’s work, seemingly channeled from Great Books, B-movies, and film noir, creates a kind of opaque, offbeat, American style poetry.

“Where the image stops and the words begin is not that clear cut,” he told me. “It’s more a give and take, a back and forth, dialectic almost in between the two. Probably more times than not when I have problems it’s because I tend to overwrite, so it’s more learning when to stop.”

* * *

Some years back I attended an art conference at NYC’s storied Cooper Union, in which Raymond was a guest speaker. With a few hundred people crowded into a small theater, Raymond ambled on stage, fumbled with the mic, and paced, stuttered, and failed to string together a proper sentence. Though a transcript would reveal little, the subtext was profound: that art can haunt, possess, torture. To a room full of law students or White House aspirants he’d have appeared tragic, but to the paint-splattered set that hung on his every utterance he was unmistakably the “real deal,” a modern day Vincent Van Gogh.

I’d heard from a mutual friend that Raymond is essentially never not working; that the thousands of books that fill the shelves of his studio and Venice Beach home are all annotated and marked up in a manner that suggests Jack Nicholson in The Shining. When I asked about this he pulled from his pocket a fistful of wadded-up pages.

“I have books lying around,” he explained, “and I take the pages out. It could be practically anything. I do a lot of reading in transit, whether it’s a car, bus, train, whatever. I don’t read for plot. I don’t care how it ends. I read a lot slower, because I’m often trying to analytically almost break down the writing as it occurs, or as it scans. In a way, it’s rewriting of a sort.”

In his 1998 anthology, “Raymond Pettibon: A Reader,” Raymond shoehorned into 352-pages what might be interpreted as his muses, or the voices he hears in his head. Marcel Proust, William Blake, Jorge Luis Borges, Samuel Beckett, and Henry James are perched at the same table as Charles Manson and Mickey Spillane. It is this commingling of high and low that makes Raymond’s work so compelling.

“Sometimes I kind of play with the whole idea of illumination,” he told writer Jim Lewis in a 1996 interview in Parkett, “as if the text was passed down from God to the lowly monks, who spend the duration of their lives illuminating it. Sometimes I almost wish I could have some kind of contract with the devil, giving away my everyday life, if that would buy me the thousand years I need to really understand the work I’m doing.”

When I mentioned that I’d been the editor of several surf magazines, and that my favorite part of the job was writing captions, he perked up.

“That’s a skill or talent that has a lot in common with what I do, he said. “(In my work) I think a lot of people consider the words dissonant from the image; that they’re just thrown on randomly. That’s not the case.”

“Is there a specific headspace you’re going for?” I asked. “Does it come from walks, 3 a.m. epiphanies, hangovers? Or is it simply your whole life?”

“It was, or has been at times, my whole life,” he told me. “That’s not the most attractive thing to say, there are other things to do—go out in the water, for instance. Life should be complimentary with art. But the one can crowd out the other. It can be so time-consuming. I have more work in note form than I could ever get around to doing—enough for several lifetimes. I could be king for a day, and I’d still want to get back to the work. And that’s not pushed by any puritan work ethic or nose-to-the-grindstone kind of thing.”

“When I’m with him he often talks about his days as a professional wrestler, but I never really got into it because I don’t know anything about wrestling. But one day we were going from Long Beach to the Wiltern Theater in Hollywood to see Sonic Youth, and the traffic is horrible, and we’re stopped on the freeway, and I thought, this is a good time to bring up the wrestling career, because he can’t go anywhere, and I’m going to put him against the wall—because it’s very hard to get him on anything. ”

He looked over at Stacy, his gallery rep, who’d just arrived and quietly taken a seat on Raymond’s couch. “It’s not outwardly driven, although my gallery, with their crops and cajolements and occasional carrot, is some incentive for not doing anything else in life (laughs).”

I asked if work was his default activity, a kind of tic.

“Yeah, that’s a good way of putting it,” he said. “You know, I’ll have my notes and pages or whatever—my public behavior isn’t rude or anything. But there are always distractions. It’s actually been a long time since I had a dream or thought in the middle of the night that I felt compelled to write down. A lot of good things can come from that. But I have too much material already. It can be too intrusive. It’s a trade off between that and laziness. Every writer or artist has their tricks to get themselves into the right space. But I’ve been at it so long that it is more concealed or embedded, without having to think about it.”

“Do you have times when you want to get away from the work?” I asked. “And if so, what do you?”

“They’ll track me down,” he joked, nodding toward Stacy. “I’m always heavily escorted. You know, some people have their entourages to help them get around, to get them things, or to thug on someone, or whatever. My entourage is there to keep me from doing anything that’s not gallery-approved or what is against my better interests. I have a little envelope with the milk money in it and a little safety pin in it... No, really, it’s not that neurotic.”

We walked back to the wave painting. Raymond inspected the trough, the curling face, the snowy lip.

“I come from realism,” he said. “That’s my model, my default. But to do it justice it’s going to stray. I mean even with this, the wave, it’s painted vertically on the wall, the drips weren’t planned or anything but they don’t detract either. But I still don’t know how it’s going to turn out exactly. It’s getting there with some confidence, but I could always mess it up. With this sort of thing I think of the image of Turner, the great landscape painter, painter of the sea, having himself strapped to the mast of a ship while it went into the storm, experiencing that as to better describe it. His sea paintings approximate or tend toward the complete abstract, but that’s still an act of realism, of understanding reality, or at least a sincere attempt to.”

Raymond stared at his wave. There was nothing in the frame to gauge its size, but judging by the look on his face it was at least three times overhead.

And he’d yet to even start in on the text.