Hot New MFA Grad Wants To Show You Her Wet Paintings

TART CARDS

Words by Ernie van Amstel.

Those of you who use the phrase ‘born too late’ or insist that you would be more suited to another era- probably the one with the best music, parties and celebrity- the 70s’ and 80s’, I’ve got news for you.

Bridget Stehli means it more than you. She says words like crustpunk and Sinbad without consideration.

Her devotion to this time proved to be more than cosmetic upon my visit to her home last week. Her world is heavily attended to by an atmosphere that was championed in those final dying decades of the last century, and I mean this in less of a Tupperware party, Jello-mould-dinner kind of way and more of a Judas Priest, Huxley-doing-ether-in-the-Chateau kind of way. Minted pairs of sunglasses sparkle on laminated surfaces everywhere, and fibreglass paintings of unicorns adorn her walls. There are shaggy carpets you can imagine Eve Babitz fucking on, piles of books, VHS, vinyls. And there's metal. So much Metal. Heavy, acid, satanic, wicked, obscure, adored.

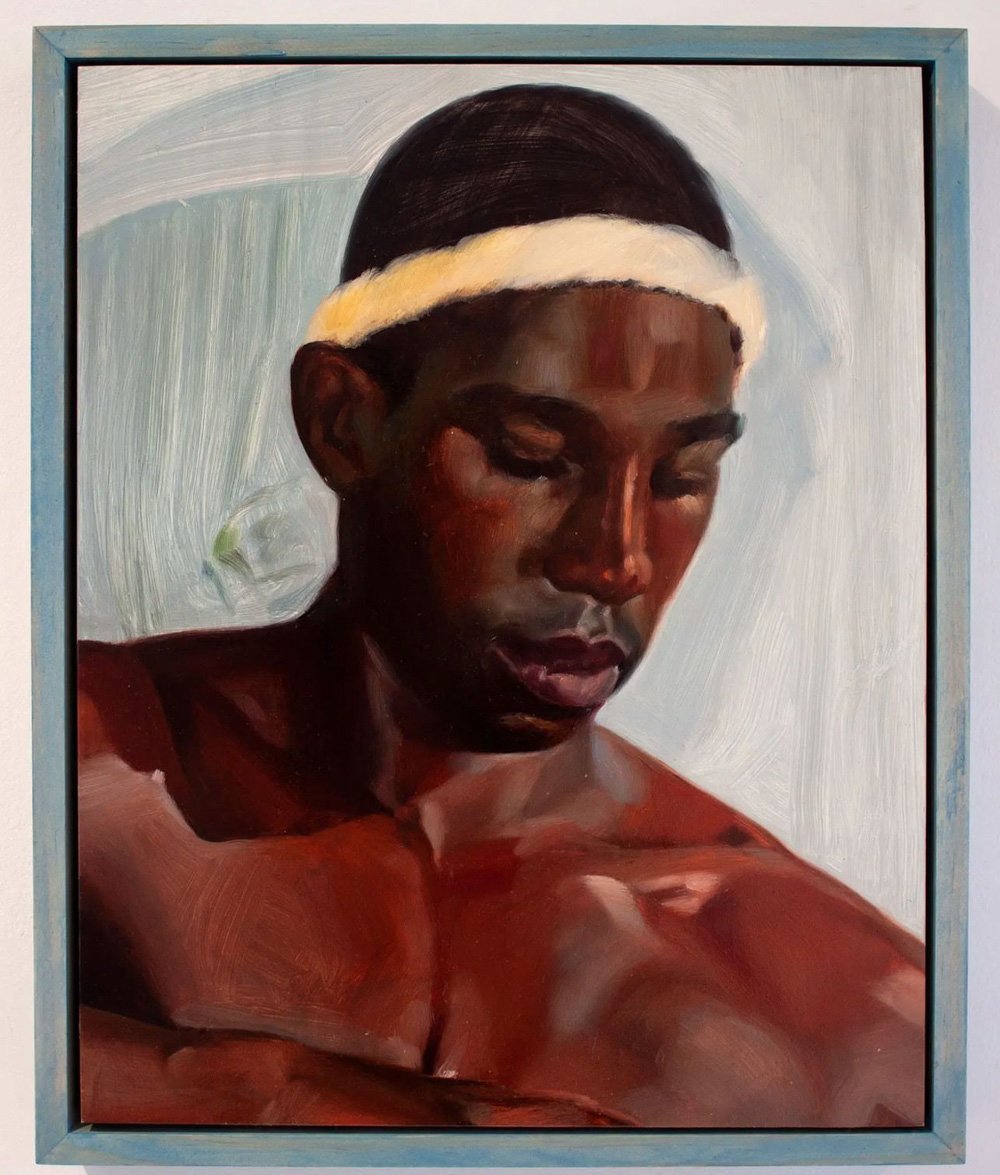

‘DAVID WATSON’

We talked as she unpacked her dishwasher (the only prevailing item that betrays her ecosystem), which I’ll divulge was packed with delicately painted retro mugs. You probably think my obsession with Bridget’s environment is bordering on surveillance at this point, but it’s relevant because the thing is, she is a dedicated scholar of the discovered beauty. She earns her information - a characteristic that could be considered exotic in this day and age. Her home is just a symptom of her work. She enjoys narrative, and not in the way most people do. Curation, in the purest sense, is the act of allowing material to tell its own story. To not undermine the imagination of those who enter your world by explaining everything. Rather, the items in Stehli’s world make the context. They explain themselves.

‘One of the best things about living in this age is hindsight.’ I have to agree with her. Her art, also, agrees with her.

TART CARDS

The spectacle of the world pre-internet, with its appeal to the grime and glitter, its disregard for standards, its provocation of desire and volatility, and its worship of sex and freedom, is in many ways the well that Bridget impressively draws from. Henceforth, when you look at a Stehli nude, such as ‘TJ Swan’ in the throes of pleasure, you won’t see stamina, power or even porn really - You’ll see something more disarming, something stranger. For me, it was a man seen by a woman.

So much of the human (especially the female human) experience is tied up in being seen as the symbol first and the individual later. The beauty, the clothes, the gossip, the face. Or perhaps even the ‘petite’, ‘new’, ‘busty’, ‘rampant’, or how about the ‘sexy rear end’ that ‘needs punishing and then pampering’ (in that order)?

‘Untitled (3 Course Meal)’

These are all excerpts from Bridget’s post-grad body of work ‘140 advertisements from UK telephone booths, 1995-2000’. Stehli mounted 140 cards made by sex workers in London and presented them gridded and framed. Numerically ordered - another testament to her belief in material and not the ego of analysis and organisation. They were deposited in photobooths as a kind of calling card, each with different numbers, advertisements and services. These cards, lovingly referred to as ‘Tart Cards’, were made at a time when a major shift in autonomy and power coincided with the abolition of the Post Office Act in 1984. Sex workers coming out from under the thumb of pimps and institutions used this loophole to evade prosecution, littering the streets with these cards. The longer you look at them, the more susceptible you become to the work’s secret fascinations. Many of the images are not actually of the women who made them; some have had their numbers scratched out and amended. Others lean into categories - racial, post-op, pre-op, age etc. And at about this point, you realise that Bridget knew all along about our human tendency to see the symbol before the individual, and so did the women who made these cards. A symbol that they can now exploit every bit as ruthlessly as any of the men do.

‘TJ SWAN’

Bridget’s Demi-Monde! We are all pinups on the surface and artists underneath! Her art stays loose and maintains its cool. Throughout the course of our afternoon, she said so many sick things I became averse to writing them down on my spirax for fear of interrupting something profound. And as we were wrapping it up and I stood in her light-filled studio out the back examining a VHS of a film called ‘Born Innocent’, the byline reads, ‘with LINDA BLAIR, star of THE EXORCIST’. And I think about 14-year-old Linda masturbating with a crucifix, and I think about how one of Bridget’s salvaged cards says ‘young and foolish’, and I think about how generally unfoolish women are. I’m thinking about myself, and I’m thinking about history, and I’m thinking about myself in relation to history. So much is left out. The anxiety of information lost haunts me. Why are we sometimes scared to communicate across social boundaries? To lean into other lives, other times, other worlds and make art about it? Do we exist primarily as categories of humans or do we have a common duty to regard each other? Sometimes revealing alternative narratives and counter-cultures to the art world is like dealing with that little girl from the exorcist - Everything gets the bile.